-

play_arrow

WURD Radio

By Kiara Santos

How prison has shaped the lives of our elders.

As Michael “Smokey” Wilson, 70, walks into the middle of a community-news workshop he proclaims for all to hear in his signature passionate, thunderous voice, “My name is Michael ‘Smokey’ Wilson. I served 46 years, six months and one day in prison. I am a returning citizen.”

Wilson was incarcerated when he was just 17 years old. He has been in 11 different foster homes from the ages of 6 to 16 years old.

He has charted his own path as a talented boxer, coach and one of 2,500 men released from prison in the United States who were sentenced to life/death sentences as juveniles for murder cases. He had been denied a pardon four times in jail.

A U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 2012 found that even when a juvenile was convicted of murder, a judge must be allowed to take a juvenile’s age into account (along with other relevant circumstances) in deciding the appropriate punishment, according to the ACLU.

The court decision ruled in 2012 in the Miller v. Alabama case that it was unethical, and found that it violated the Eighth Amendment, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

He writes over text: “We can do more, and we will. I hope to position myself in the Philly government in some position. Hopefully, that would connect me with others who really want to make a change in our community and for the Black lives who live in Philadelphia.”

Between loved ones and those incarcerated, they have missed birthdays, holidays, inside jokes and much more, serving decades in prison for crimes that are deemed conclusive. For some, they must watch their kids grow up without them. Each visit they see their kids grow into people they cannot recognize.

Many men like Wilson wound up in prison after they say the justice system failed them. Some were finally released, but others are still serving time know their death will be their incarceration.

According to the U.S. Health Affairs, in 2020, 14% of male prisoners and 9% of female prisoners — a total of 165,700 people — were ages 55 and older. It is estimated that by 2030 older people will represent fully one-third of the entire prison population.

In cases like Wilson, he says there is more than just the grievance of prison, but the grievance of watching life go by.

Wilson says: “There’s a whole psychological and biological change when growing older especially inside the wall. Think about it, you’re living in a very different atmosphere, your whole experience is different growing up behind bars. I didn’t grow up knowing the experience just being around women or raising children.”

According to the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge: Philadelphia Prison Population Report, Black Pennsylvanians are now about seven times more likely to be in state prison than white residents. In Philadelphia jails, Black people are detained at a rate nine times higher than white residents.

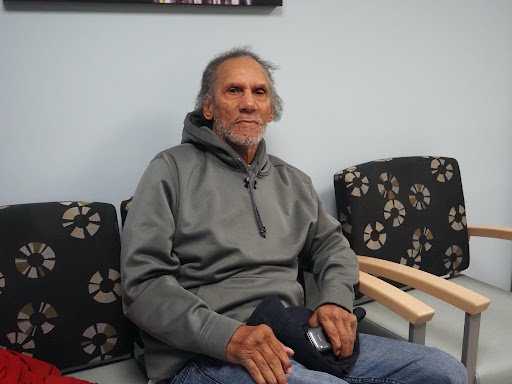

Wilson served his 46 years starting in 1970. His longtime friend Wali Beyah, 67, (Beyah changed his name from Brian Wallace to Wali Beyah when he converted to Islam in prison; Wali means “protector” in Arabic.) served 46 years and was arrested for homicide and robbery. They met in prison as juveniles assigned to certain block of cells. However, Beyah was jailed when he was merely 14 years old.

Wilson was a part of a gang called the “Morocco’s,” he says. Wilson, in fear, allegedly shot a 15-year-old kid in an opposing gang. He was arrested shortly after and had been in prison since 2017, despite the ruling being finalized in 2012.

Wilson and Beyah discuss how they were merely two boys who were arrested nonsensically. They feel the insurmountable pain of no life transitions. No kids to talk to, seldom friends who are alive anymore and nothing but memory to keep them alive, Wilson says as Beyah bows his head down, tears forming and silently nods in agreement.

When Beyah speaks, he speaks calmly. He only answers questions that he is comfortable with sharing. The other questions elicit him to silently cry in reflection of the youth and aging he and Wilson were stripped of for 46 years.

When seeing Beyah in distress, Wilson states: “Some of us can talk about it — some of us are running from the past. From the anger.”

Wilson then elaborates on his experience: “You got all these young Black boys going to jail at 14, 15 years old. They’ve been in jail for how long? Who is y’all? But they did it in an articulated law … a person’s brain doesn’t begin to develop until about 25. So how do you hold that against them? How can a juvenile a premeditated, willful, deliberate, and malice murder? It just doesn’t make sense.”

Wilson has made a name for himself despite the prison sentence. He was formerly covered in the New York Times amid his sentence for being a mentor for Bernard Hopkins, the esteemed, undisputed middle weight champion of the world and three time light-heavy weight champion of the world.

When Hopkins and Wilson met, their love for boxing brought them together. Wilson, who is blind in his right eye, recalls one of the first conversations with Hopkins: “He asked me, ‘How’d you lose your eye?’ I told him someone stuck their thumb into it. A man named Artie ‘Moose’ McCloud. He responded, ‘That’s my mother’s brother.’”

Twenty years after their encounter, Hopkins was released from jail and training for a fight in Las Vegas.

At a news conference to promote the fight with against boxer Oscar De La Hoya, Hopkins pulled out a photograph of him and Wilson in 1985 and waved it around. On the back of it, Wilson had written to Hopkins, “You will be the middleweight champion one day.”

Wilson now spends his time working on his own non-profit, boxing training and a documentary on his life experience. When he walks down the street or stops into a restaurant, a sporadic person will stop and ask him if he’s the Smokey Wilson they have heard, read or watched about.

Tackling Aging in Prison

The Pennsylvania state prison population is getting older. The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections defines an “elderly inmate” as being over 50. However, aging is prominent before they even reach 50.

The 2022 Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s Department of Corrections budget testimony found that a decade ago, this age group accounted for roughly 10% of those in state prisons; now it is 27%.

Among them, nearly 2,000 are over age 55 and have already served at least 25 years. The vast majority are serving life without the possibility of parole, according to the budget testimony.

In 2021, Spotlight PA found that the State Correctional Institutions in Laurel Highlands and Waymart, where individuals requiring long-term care are imprisoned, accounted for 9% of the entire prison operations budget — $204 million. The two facilities house only 5% of the state prison inmates.

“Good Brother” on death row

James “Good Brother” Lambert, 72, spent 33 years on death row for two death sentences — two capital death punishments. One of his favorite songs that he felt resonated with his life story is Earth, Wind, and Fire’s “That’s the Way of the World” — an R&B song that he says he always felt was his life story summarized.

The lyrics read: “Plant your flower / and you’ll grow a pearl / Child is born / with a heart of gold / way of the world / make his heart grow cold.”

Lambert spent 42 non-consecutive years incarcerated for other crimes. He was born in South Philadelphia and raised in West Philadelphia by his aunt and uncle — his father’s brother – since his mother felt incapable of continuing to raise him when he was 3 years old, and his father had passed.

Lambert says: “ was always in my life. Even though she allowed my aunt to raise me because I think she was going through a lot of traumas at the time; she was pregnant, and my problem at those dates was that she got pregnant with my sister and at that time I was real sick.”

He was diagnosed with a rare kidney disease at this age, Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease.

According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, ARPKD “is a rare genetic disorder that affects 1 in 20,000 children. A fetus or baby with ARPKD has fluid-filled kidney cysts that may make the kidneys too big or enlarged. ARPKD can cause a child to have poor kidney function, even in the womb. ARPKD is sometimes called “infantile PKD” because healthcare providers can diagnose it so early in life.”

When Lambert was ill with ARPKD, it was something not easily detected, let alone treatable. The doctors told him he wouldn’t live to see 7 years old. He thought he was going to die young, yet he beat the odds.

Lambert says: “I had major operations when I was 2 to 4. Whatever was wrong, my kidneys, they doctors claimed that my prognosis was that I wouldn’t see my 7th birthday. Me and this other guy, who’s got the same medical condition, told us at children’s hospital that we both we wouldn’t see it. We did.”

The layers of his life expose how society had failed him, how it had been set-up for him to become “incorrigible.” A non-active mother, truancy cases, punitive school measures and a complex family life, he says.

Incorrigibility is a term used for delinquent youth across the nation. It is known as habitual disobedience of a parent/guardian.

It is where a child habitually disobeys the reasonable and lawful commands of the parent/guardian, according to AZ Court Help.

Lambert recalls his mom, who has been present but not directly parenting him, reporting his truancies in school that led him to a juvenile detention center and getting kicked out of 10th grade for fighting.

Lambert then moved from Coatesville and Philadelphia interchangeably for years. He was also drug addicted, which led to his nickname “Good Brother,” a man “with a heart of gold” he says, referencing the song.

Lambert says: “My best friend Barbara … she motivated me to stop getting high. She just looked at me and said, ‘Aren’t you tired? We should build together.’ I was shoplifting and all that with my wife at the time. I had a lot more than what I had because I have potential. I had potential to do anything I chose to do, and the intelligence to do it. So, she started calling me good brother.”

Lambert spent time in “the belly of the beast” he says, and in solitary confinement within the “beast”. He talks about how it has given him the time to reflect on his life. He was able to marginally escape the most extreme degree of confinement by working in his prison’s law library.

When in imprisoned, Black people are more likely to end up in high-security settings.

In Pennsylvania, 53% of men in prisons designated “maximum” or “close” security are Black, an Inquirer analysis of Department of Corrections data found, whereas Black people are just 36% of minimum-security prisoners.

In Restricted Housing Units, like James’ cell, is where prisoners get only five hours a week out of their cells.

The male population is 58% Black.

More than 80% on the Restricted Release List (RRL), a list of all inmates held in solitary confinement indefinitely and contains inmates all condemned to segregated housing indefinitely, are Black.

Lambert maintained a “healthy image” to fend off any extra punishment he could’ve received while in jail, he says.

He prides himself of little write-ups or interferences with the guards within jail — especially solitary confinement. He talks about how it must be acknowledged he was able to work in the prison’s library despite his capital punishments to death row.

Due to the work of lawyers who had tackled Lamberts’ case, they were able to find he was not accountable for the murder convictions he received, he was then released.

The day after he came home, he found himself at the Aging People in Prison Human Rights Campaign, Philadelphia chapter (APP-HRC).

He has been working with them ever since his release.

The Philadelphia chapter had lost its stable office space in Germantown’s Center in the Park. However, the Founding Director, Tomiko Shine, explains how she manages to reserve the space once or twice a month — contributing to the lively events that happen within the center, she says.

Tyronne Morton or “Brother Ty,” 74, served 20 years for second degree murder, one of those years in solitary confinement. He is the advisor for APP-HRC and husband to Shine.

He talks about his experience in prison and compared the system to a modern form of slavery.

Morton said: “American prisons started to rise after the Civil War. There’s surveillance all over Black neighborhood. Young kids get arrested and they’re forced to work. It’s about control of Black bodies. The system seems like it’s changing but it’s just adapting to modern times.”

He refined his life after incarceration, he speaks on how he realized how prison was a scam — and how he had to get out of it.

He says: “I saw the situation I was in. I (was) in my older 20s and I told myself this is horrible. I don’t want to end up like these older men. I don’t want to spend the rest of my life in here. I went up to seven times for appealing for parole. I told myself if I appeal one more time and I don’t get it, I’m just going to escape. On my eighth time, I got parole.”

After his release, he obtained a degree at Bowie State University for psychology.

He now works with his wife, Shine, to help release other aging prisoners.

Compassionate release

Pennsylvania’s compassionate release law has stifling restrictions that make it difficult for prisoners to utilize to leave prison.

According to the PALawHELP organization, the policy allows aging inmates, who meet the most repressive requirements, to be transferred from prison to a hospital, long-term care facility or hospice. To be granted compassionate release under the current PA legislature, individuals need to prove, among other things, that they are so gravely ill that their death is imminent and that they need care that is better provided outside of the prison.

In practice, and according to a recent investigation by SpotlightPA , 31 people were granted compassionate release in the last 13 years.

Furthermore, in the 2022 Pennsylvania Commonwealth budget testimony, the average cost per person for medication alone is nearly $3,000 a year for aging prisoners. This is more than double the cost for those under 50.

Lambert’s work with APP-HRC is to help release aging prisoners nationally, and to help them transition smoothly back into society, with as much communal aid as possible.

APP-HRC provides legal counsel for current inmates as well as training sessions once they return home. This means providing them assistance with clothes, rent, food and technology, and even how to create an email address or apply for jobs, its voluntary IT officer, Brandon Walker, says.

Alongside the food drives hosted by Shine, the center holds pottery classes, salsa dance lessons, movie watches, hot lunches and a place for rest and socialization for Germantown’s elder residents, Shine informs.

The Center in the Park is a significant location noting the history of abolition in the Philadelphia neighborhood, Shine states.

At APP-HRC, everyone is referred to as “Brother” or “Sister”— an affirmation and reminder that we are more connected than we think, Shine says.

The former and currently incarcerated individuals all tell their stories with no hiding the crimes they have committed. They share their stories with others like icebreakers before a class begins.

When Wilson was introduced to Lambert at an APP-HRC general meeting, they hug tightly — remembering that they once met on the streets of Philadelphia together in the late ’60s, reunited during their prison sentences and again at the Center in the Park.

“I remember him from our time back , you might know him as Brother James, but to me, that’s Monk!” Wilson says.

The current incarcerated

The inmates still serving time carry themselves not as purely innocent people. They know what they have done, but it does deter them from thinking about release.

They fight for their right to humanity. They all speak on the fact that they understand in a much more nuanced way how much they deserve empathy and release.

The system has told many of them they are incorrigible and has marked them with death by incarceration — life without the possibility of parole. The experience of prison is hard to articulate for them, but they work to make sure the stories of those formerly and currently incarcerated are told. They all — incarcerated and formerly — testify to their belief of the exposure.

“That’s why I’m the way I am — alive.” Wilson remarks.

Wilson continues saying: “ these brothers got out. I tell them what I can do to work with them. I tell them ‘You can do anything you want.’”

Lin Thomas, “Brother Amin,” of APP-HRC testifies to this sentiment too. His cousin Robert Joyner, 80, is serving a life sentence for fatally shooting two police officers in Philadelphia in 1970.

Joyner and four other men were sent to jail for shooting two police officers (one survived), according to a Plough article about Joyner’s militant Black Panther Party/”The Revolutionaries” partner, Russell Maroon Shoatz.

According to the Plough article in 2014, Shoatz was released from 22 consecutive years of solitary confinement into the general prison population. The time spent is 21 years and 50 weeks longer than the length of time in solitary the United Nations has deemed to be torture.

Thomas speaks on behalf of Joyner, who cannot talk for too long due to his health, speaking too long throws him into a fit of coughing.

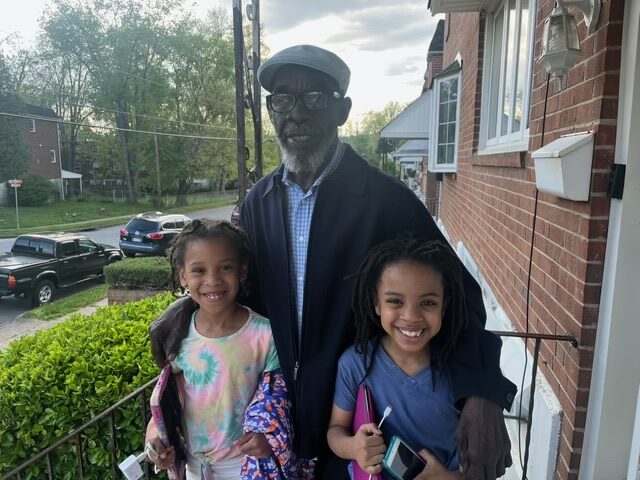

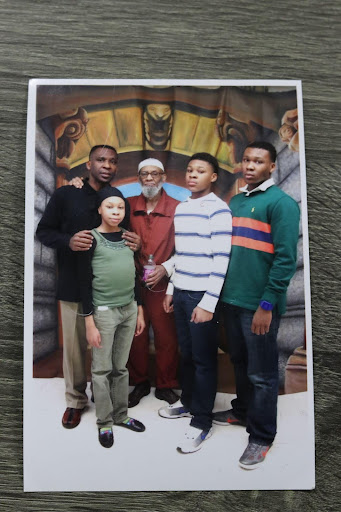

Thomas carries a photo of an older man in a kufi (a woven brimless hat popular in Middle Eastern cultures), an orange jumpsuit, and a face that has been hardened through time in jail. The photo, now aged, shows Thomas’ kids and Joyner standing tall in the center of the photo, where they visit him at SCI-Phoenix, formerly known as SCI-Graterford, in Collegeville, PA.

Joyner’s story of incarceration begins with the civil rights movement and protests that happened across the nation during the late ’60s and amid former Police Commissioner then Mayor of Philadelphia, Frank Rizzo.

Thomas says: “That’s what you all got to understand what’s going on in the ‘60s and ‘70s and is a victim of that because his life got sacrificed for a lot of other lives to give people today opportunities. They did studies after the riots, the police force seemed to be an occupying party, and that Black folks had been excluded from many different opportunities. But unfortunately, he’s stuck in the system. Was his act a criminal act? No, it wasn’t a criminal act. It was a political act.”

According to the Plough article, Sgt. Frank Von Colln and Patrolman James Harrington (who lived) were shot about a half hour apart from each other. An unidentified man fatally shot Von Colln five times. No clear evidence was ever found to identify the shooter in either case.

Yet, in his autobiography Shoatz admits to being “at the immediate scene of those events” and claims that the acts were “carried out in accord with and at the behest of the leadership of the Black Panther Party.”

According to an archived and digitized New York Times article in 1970, Commissioner Rizzo issued search warrants for a Black Panther party raid based on information obtained from a suspect arrested and charged with the murder the day of Von Colln, the 43-year-old member of the park police unit.

Temple archives show that Von Colln was a park officer, sitting at his desk when shot.

Joyner and his brother Alvin Joyner and three other men were arrested.

According to the Times article, “Rizzo said that the Federal Bureau of Investigation had joined the search for the three other Blacks. The commissioner said that (Williams was considered in the Times’ reporting to be the ringleader) had ‘voluntarily’ told the police that he and the five others conspired to ‘kill some pigs’ and blow up the Cobbs Creek Park guard station manned by Sergeant Von (Colln).”

The Inquirer article published in 2016 reported that Shoatz, after 22 years of solitary confinement, won $99,000 in a settlement after lawyers for the Pittsburgh-based Abolitionist Law Center sued the state in federal court. They contended that Shoatz’s solitary confinement violated the U.S. Constitution’s Eighth Amendment ban on “cruel and unusual punishment.”

While serving time in prison, Shoatz had escaped from prison three times, knifed a guard, and when he escaped, he kidnapped a guard’s wife and child and tied them to a tree.

The Inquirer article reported that Kurt Von Colln, 65, one of three surviving children of the sergeant and a retired Philadelphia police officer himself, is against reconciliation with Shoatz, who had mentioned an idea to hold a forum between former Black Panther members and police officers.

“No way,” said Von Colln, “This guy doesn’t deserve it.”

Von Colln said to the Inquirer that the elder Shoatz has “taken a lot away from the Von Colln family.”

Furthermore, Von Colln called the state’s $99,000 settlement with Shoatz “completely ridiculous. This guy is in there for killing a police officer and he’s not been a model prisoner.”

Today, the Von Colln memorial playground stand a few streets away from the Philadelphia Art Museum.

Joyner has suffered grave health issues and was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or COPD, which resulted in him to undergo extensive surgery that cut off a part of his lung, Thomas says.

He is perpetually ill and weak, yet prison doctors have neglected his recovery process and remains in a cell at the high-security prison, Thomas says.

The people at APP-HRC are working to get him out through the compassionate release law in Pennsylvania, Shine and Thomas say.

“This is really a matter of public opinion. It’s a matter of political policy. was a time in Pennsylvania, back then, when a person had a life sentence. They were eligible, in maybe, 13, 14, or 15 years to be released — with a life sentence. Then, what happened was the politicians pretty much put them in jail and threw away the key,” Thomas said.

Inmates at SCI-Phoenix

Carved out of 164 acres of farmland, the State Correctional Institution Phoenix is notable for its scale. According to the Inquirer, it was built to replace the aging Graterford prison, which replaced the even older Eastern State Penitentiary, which replaced the Walnut Street prison. Each was, in its time, the largest and most expensive prison built in Pennsylvania.

Brian Charles, 50, is there and is in the 30th year of his life sentence in prison for homicide and robbery.

His vibrant voice can catch anyone’s attention — even through a muffled phone call from prison.

For Charles, too, health plays a large issue in the many inhumane aspects of incarceration. Yet, Charles sees the problem of health and its ties to incarceration as a larger, systemic issue, he states.

The poverty rates, the food deserts, the lack of access to healthcare, the racial profiling and the lust for wealth are what Charles says he believes put Black people — whether directly or indirectly — in jail.

Charles says: “A lot of it is rooted in poverty and being hungry and thirsty for money. Many of these crimes are rooted in some monetary gain. Money is at the root of it. I think about nonprofits that offer to young people this desire; the way people pursue money is the error. There needs to be financial responsibility.”

Charles has kept himself physically active and is a self-proclaimed activist, even behind bars. He works out and keeps his body in shape, noting the ability to get out of his head even for an hour while he exerts his body. He protests the quality of food within the prison, he says.

He states: “The lasagna you think of is not the lasagna we have here, it’s what leads to some guys having health problems later… the health elements that are common are hypertension and high cholesterol … it’s because of the food we have access to, and we don’t have access to … the food they serve us, and meals aren’t what they described. Often, guys don’t eat the normal meals and revert to the commissary. The food in the commissary is high in sugars and is all processed. Eating that food for years is not good for you. So, I’ve been trying to get them to change the food.”

Charles exemplifies resilience behind bars. While he ages in prison, he notes the transitory periods he has been stripped of.

“When you have this big transition, people have this snapshot of what they were then. An isolated incident that this person did. What I want people to know is that that snapshot is not who I am today. Having some life experience and self-reflection I can see the errors in my life. I have a lot of growth and maturity and try to pass that along to the young people here . This isn’t a narrow path forward.”- Brian Charles.

Solitary Confinement, “The belly of the beast”

Prisoners who don’t follow the rules can wind up in “the hole,” as many of the men here call it.

‘The hole” is solitary confinement that the correctional officers can throw you in based on their own desires, Lambert says. For many of the former and current inmates, they can all testify to their pride to avoiding the hole — but it still came with a cost.

The Inquirer reports that the Pennsylvania DOC RRL, according to DOC policy, have reasons for being placed on the list could include a history of assault, escape attempts, and “threat to the orderly operation of a facility.”

The Intensive Management Unit (IMU), a 22-hour-a-day lockdown unit, offered a path off the list and into the prison’s less restrictive general population cell blocks. Inmates will have to work to earn that privilege, though it is not clear how or when.

Inmates describe a scene of only receiving a few hours a night of distressed sleep with lights on 24 hours a day. Stale air and soured more if a desperate prisoner should take to smearing feces or throwing urine.

A consistent flow of maddening noise of unseen neighbors kicking and shouting in their cells. And, in those identical cells, four out of five prisoners would be Black, in a state that is 80% white.

The IMU is Pennsylvania’s latest venture into long-term solitary confinement — what inmates call a “the hole within the hole.”

In 2015, the state also settled a civil rights lawsuit by agreeing to move seriously mentally ill prisoners out of Restricted Housing Units, where prisoners received five hours a week out of their 10-by-8-foot solitary confinement cells, into new treatment-oriented lockdown units that promised 20 hours a week out of cell.

“You can’t have an emotional breakdown,” said Mark Williams, 33.

Williams, who is serving his 13th year of a life sentence at SCI-Phoenix, was arrested for first-degree murder.

Williams says he works hard to make sure he does not fade into oblivion. “I’m already gone,” He states over a time-limited call. “There’s no redemption.”

Williams, keeps his tone calm despite the precise articulation of rage in his words.

“The experience of aging in prison is so strange because you can’t age right. Time is standing still. Time is passing but standing still at the same time. You’re not having those experiences that mark those transitions. I had no opportunity to change from a teenager into an adult … when you’re not a certain age around certain people … you miss that. It’s uncomfortable. Once I became 30 years old, times I couldn’t get a gauge of how old were because I was never younger, around people 30 years old.” – Mark Williams.

Williams has recounts how he has lost aunts, nephews, cousins and friends as he serves his death-by-incarceration sentence. It is what he has felt is the only true distinction between him and the younger inmates or newly incarcerated who come into the correctional institute with him.

“Only time. Over time, I had more experiences,” Williams says. “The loss of loved ones. The changes you go through … it changes you.”

Furthermore, the loved ones he still does talk with are even further away from him. There are limited communication modes due to COVID-19-induced visitation laws.

His mother is now nearly 100 years old. She was always able to visit him in the pre-pandemic, yet now she cannot figure how to make an account on the prison’s online visitation platform, nor can she drive herself. It has been two years since they’ve last seen each other, Williams says.

A fellow inmate only three years younger than Williams is Demanuel Coles.

Coles, 30, is still serving time for a decade-long sentence for criminal conspiracy and aggravated assault riot.

Coles, who had been in and out of prison as a kid since 15, he is serving his longest sentence now – after his probation hearing with a judge turned into a revoking of his parole and now a ten-year sentence.

He has spent his entire 20s in jail. He believes he is innocent. He has contacted city council members, the District Attorney of Philadelphia, Larry Krasner, and has filed for numerous appeals.

Zoom and limited calls are his last connections to the outside world still, he says he tunes into the radio to keep up with the trends in music. He answers all his calls at SCI-Phoenix with a small chuckle.

“I’m not a bad person. I put myself in situations where there was trouble, at the same time, it wasn’t like, that bad wasn’t that bad,” he says over a Zoom call.

Coles’ belief in his innocence is how he has been able to distinguish himself from his peers, he says. He keeps his head down, he stays out of trouble. He maintains the optics of a decent man.

He states: “It was just that I was just easily influenced, and I liked being around my friends as I grew up. In this situation right here, it’s just based upon that I was on probation. That probation was for aggravated assault, riot and criminal conspiracy. I caught this case in 2009 when I was 16. I was charged as an adult. I did 18 months on this case, on the juvenile block though. I went to trial and my lawyer said, ‘Look if you take this probation, you can go home.’ So, I pleaded guilty. I went home…well, the probation was 6 years. I pleaded guilty for 6 years. In 2012, I caught a case that was malicious loitering.”

The years he has spent has not deterred him, though. He keeps away from the drugs that trickle into the prison, fearful he will fail a drug test and his probation will be pushed back further away from him.

He refuses to entertain nonsense that the other prisoners do. He keeps his resilience no matter how challenging it is to be defeated, he says.

“In the beginning here, it was rough. Especially not trying to go to the hole, not mess up your situation with being on the honor block. It was hard to process. I was going to be here for 11 years and not talk to my family. Especially at the age of 19, it was hard for me to process this environment. You had to man-up in here. You pick who’s the right person to be around.”

Coles will see parole in July 2023 and release in November 2023.

The cost of aging in prison

These inmates’ stories tackle the value of incapacitation — preventing someone from committing crimes by locking them up — and how it maxes out.

The council on Criminal Justice published a report that tackles incapacitation, among other things, and how it is utilized to help public safety, but it is not always a direct resolution.

The “age-crime curve” discusses how the longer a sentence, the more someone ages, the less likely they are to commit crimes.

“Some may wonder, why would we even discuss the nation’s use of long prison sentences now, amid a rise in homicide rates and legitimate public concern about public safety. Because this is exactly the time to examine what will make our communities safer and our system more just,” said the task force co-chairs on long sentences co-chaired by former U.S. Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates and former U.S. Rep. Trey Gowdy in a joint statement accompanying the report.

“When crime rates increase, so do calls for stiffer sentencing, often without regard to the effectiveness or fairness of those sentences.”

A.P.P. all people persevere

The men interviewed here have been touched by the inhumanity of prison, and used the sentiment to become an advocate for reform and release of our elders. Wilson specifically had been able to find a community of other men who share his experience to some degree with the A.P.P. community, as well as frequent hangouts with Beyah.

Today, Beyah works as a trash collector and is married. He frequents his local mosque for prayer and Wilson occasionally joins him.

Lambert, Morton and Shine continue the work of APP-HRC by gathering small community events of movie watches and toy drives during the holidays.

Wilson when in prison picked up an affinity for acronyms. T.E.A.M. (Together, everyone achieves more.) L.I.F.E.R.S. (Life is not forever, remember smokey) and much more.

He asks for the meaning of A.P.P., “I like that,” he responds. “Aging people in prison, I like all people persevere.”

THE WURD WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Black Talk Media sent straight to your inbox.

BECOME A MEMBER

The forWURD Movement is your way to

protect and preserve Independent Black Media.

Written by: Associated Contributor

aging Aging People in Prison Human Rights Campaign James Lambert Kiara Santos Michael Wilson prison prison reform SCI-Phoenix seniors Tyrone Morton

Similar posts

Featured post

Latest posts

This week on WURD: Trump assassination attempt, remembering Kobe Bryant’s father Joe Bryant, Federal aid for homeowners with fixer-uppers

If Biden steps off the ticket, there is only one person who should replace him

Moving Forward: A Statement of Unity and Healing

This week on WURD: Project 2025, How to stay cool through the heatwave, Philly’s summer street cleaning

This week on WURD: Supreme Court broadens presidential immunity and punitive measures on homelessness, an organization striving for Black youth in STEAM fields

Current show

Upcoming shows

Electric Magazine

7:00 am - 8:00 am

Conversations with the Commissioners

8:00 am - 9:00 am

Dr. Paul’s Holistic Health Hour

9:00 am - 10:00 am

Saturdays with City Council

10:00 am - 11:00 am

The Murray Report

11:00 am - 1:00 pm

WURD Radio LLC © 2012-2021. All rights reserved.

Post comments (0)